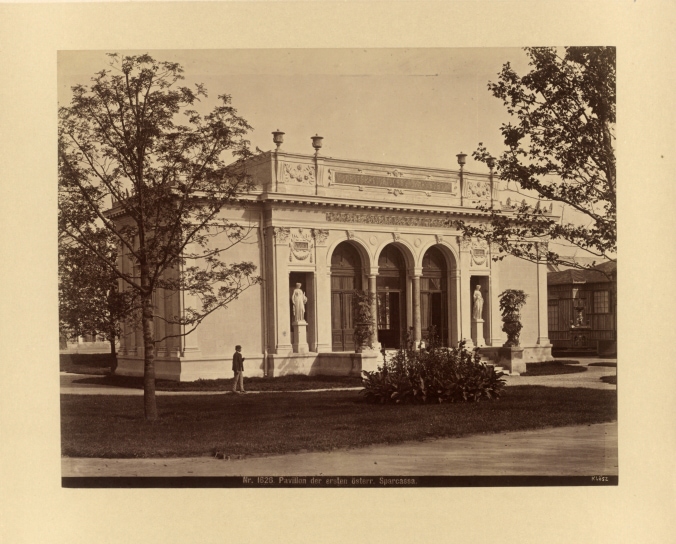

Long before we became a foundation – in 2003 – and a strong partner of non-governmental organisations in Europe – from 2006 on – we were a social business ourselves. In 1819, a group of Viennese citizens founded a private association to give common people opportunities for making provision for the future and establishing a secure and independent livelihood for themselves and their families. The association was run by dedicated volunteers in a poor neighbourhood, was innovative and obviously sustainable. It was called Erste oesterreichische Spar-Casse and was the “first Austrian savings bank”.

This is our story:

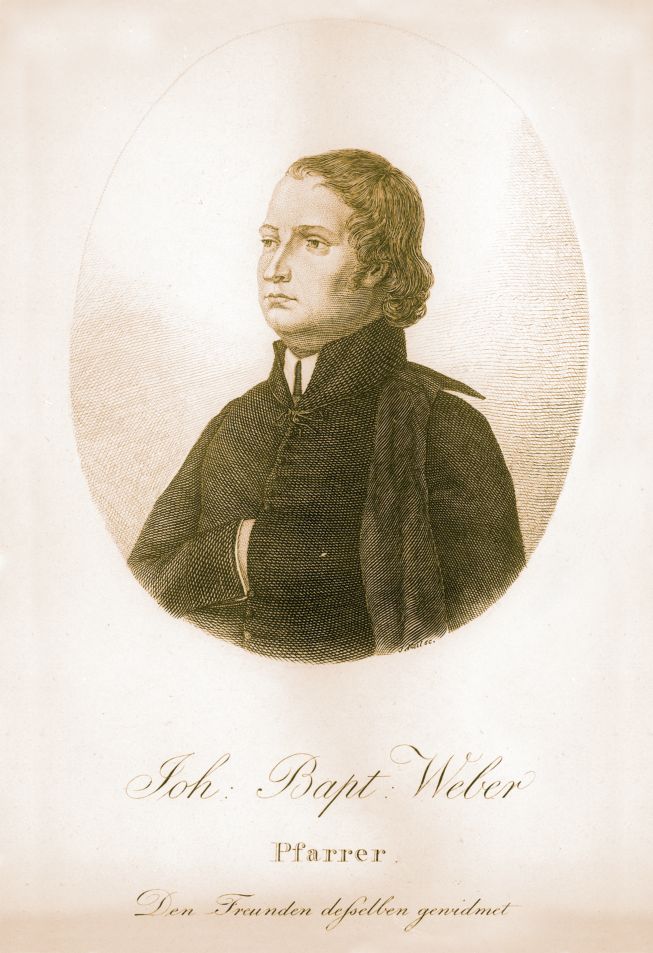

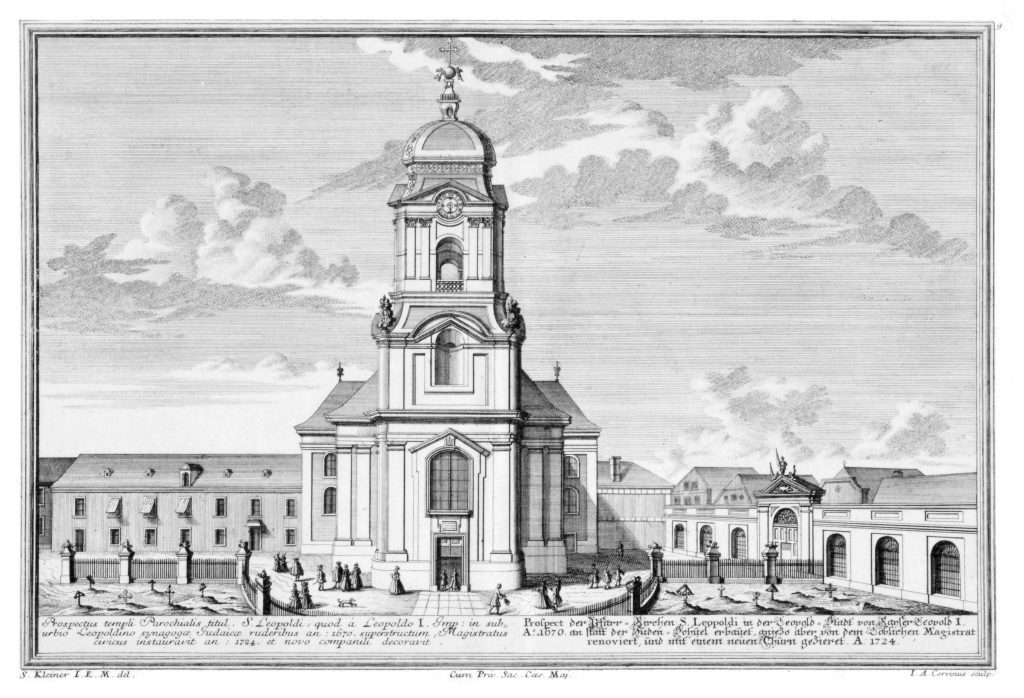

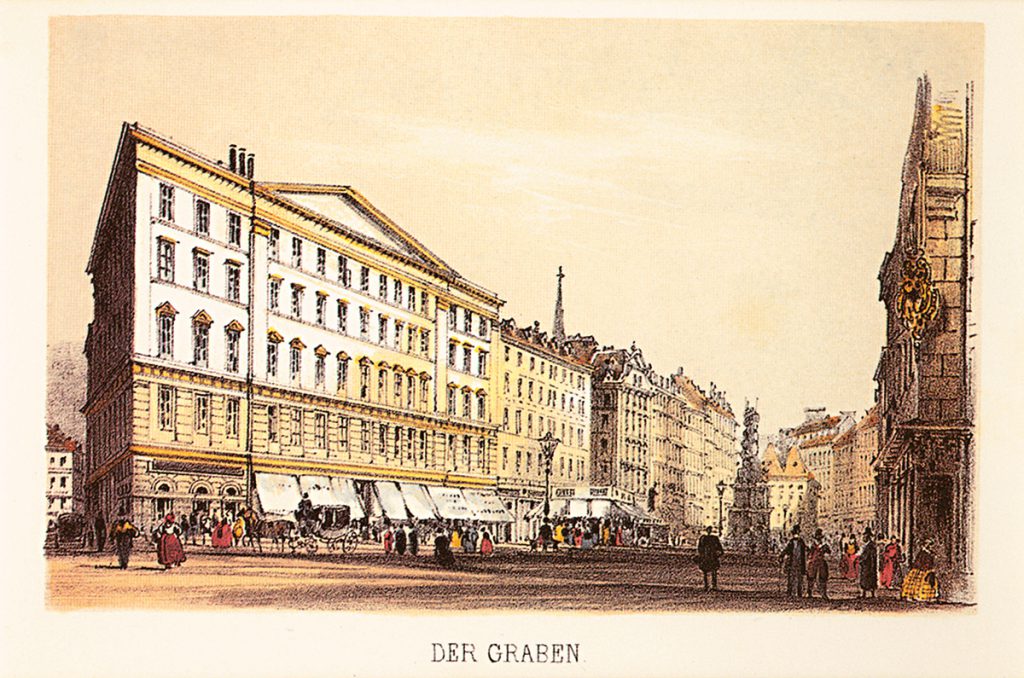

Johann Baptist Weber, born in Vienna in 1786, was a Catholic priest in the parish of St. Leopold in one of the suburbs of Vienna during the Biedermeier period. Before that, he had been a chaplain in Vienna-Lichtental, at the time when Franz Schubert performed his ecclesiastical works there, and in the parish of St. Peter in the city centre, next to which the office of the Erste österreichische Spar-Casse was to be located from 1823. A social entrepreneur before the term was even coined, Johann Baptist Weber founded several social institutions, including a kindergarten, a poorhouse and two schools, one of them for girls. He was 33 years old when he came up with the idea of founding a bank for the destitute with the help of affluent citizens.

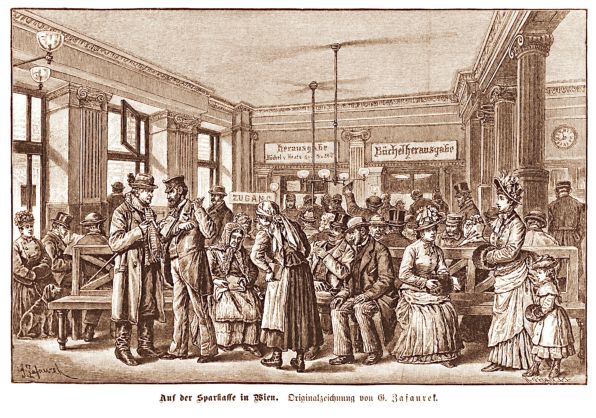

Weber witnessed the social changes caused by industrialisation at first hand in his parishes. After the Napoleonic Wars, Austria was bankrupt, and poverty ran rampant across the country. Weber wondered how he could help the people flocking from the country to the city, who now earned their living as servants, day labourers, factory workers or simple craftsmen, to live a dignified life in this world. He was convinced that just being charitable was not enough. Therefore, he asked affluent citizens in his parish in St. Leopold to pledge 100 to 1000 guilders for the creation of a savings fund. In 1819, the savings bank association already had 55 members, whose deposits laid the foundation for the Erste oesterreichische-Spar-Casse, which opened on 4 October 1819.

Weber did not stay in Vienna’s Leopoldstadt district for much longer after the founding of the Erste oesterreichische Spar-Casse: following another stint as a priest in Mannswörth, he became chaplain at Schönbrunn Palace. Weber died in 1848 at the age of 62 in his hometown and was buried at the cemetery of Altmannsdorf.

Bernhard Baron von Eskeles was also a founding member of the Erste oesterreichische Spar-Casse. He was born in Vienna on 12 January 1753, the son of a rabbi. Bernhard Eskeles the Elder died in the same year. The son moved to Amsterdam with his mother Hanna Wertheimer at the age of 17, where he got a job and commercial training in a trading business. He was already running his own business by 1770 but returned to Vienna in 1773. He became a partner in the trading house of Nathan Adam Arnsteiner and his brother-in-law Salomon Hertz, the wholesale and banking house which soon operated solely under the name Arnsteiner & Eskeles. Its business encompassed the insurance of state bonds, the financing of infrastructure such as the rail connection between Milan and Venice, financial transactions, moneylending, and military contracting. Through these activities, the bank came to occupy a central position within the state apparatus of that period. Eskeles made a name for himself as a consultant to the Emperors Joseph II and Francis II. In April 1815, he signed a petition to Emperor Francis I to grant Jews in Austria legal equality: the petition was denied. In the following year, 1816, Eskeles co-founded the Austrian National Bank and became its first director and vice governor. Three years later, he and Johann Baptist Weber were among the founders of the Erste österreichische Spar-Casse.

Bernhard Eskeles’ private wealth was significantly increased through his marriage to Cäcilie Itzig from Berlin, a sister-in-law of his partner Arnsteiner. He used it to grant large loans to the Austrian state during the Napoleonic Wars. For this reason, Eskeles, who had already been granted nobility in 1797, was made a knight in 1811 and a baron in 1822. Eskeles contributed significantly to the organisation of the European money market, as well as launching several charitable foundations. In 1820 he acquired the Palais at Dorotheergasse 11, had it thoroughly renovated and, with his wife Cäcilie, made the salon a meeting point for representatives from art and science. During the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15, Talleyrand, Hardenberg and Wellington were among the guests who also were frequent visitors at the city’s most famous salon, hosted by Cäcilie’s sister Fanny von Arnstein. Today, Vienna’s Jewish Museum is housed in the Palais Eskeles.

Baron von Eskeles died in Hietzing, then a suburb of Vienna, on 7 August 1839. He is buried in the Währing Jewish Cemetery. To quote an obituary for the 87-year-old: “Bernhard Baron von Eskeles, the leader of one of the first and most honoured trading houses in Europe, the main founder of the Austrian National Bank, of which he was the director, the man whose integrity has become almost proverbial, whose house was the gathering place for all that was outstanding in Vienna, strangers and locals, nobles and lower orders, from princes to poor artists: he started life as a poor Jewish orphan.”

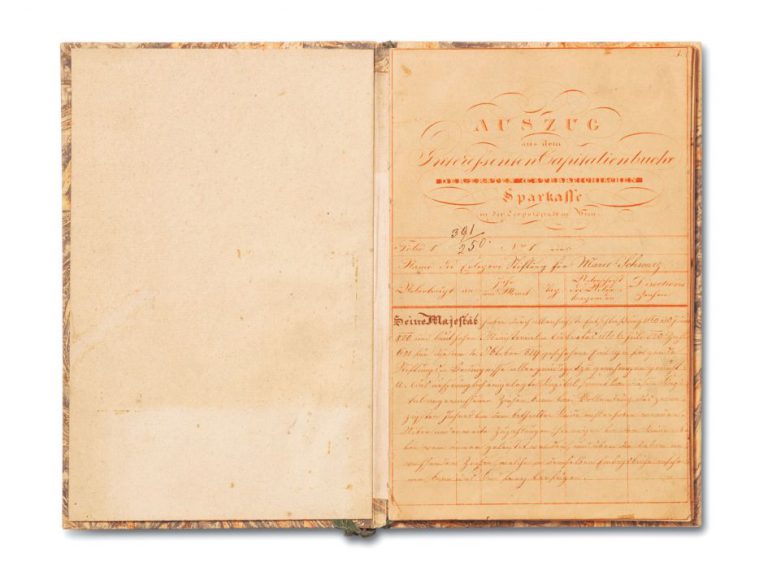

Savings Book No. 1

Erste Österreichische Spar-Casse, 1819

The very first savings book of the Erste Österreichische Spar-Casse, issued 1819, belonged to a woman: Marie Schwarz.

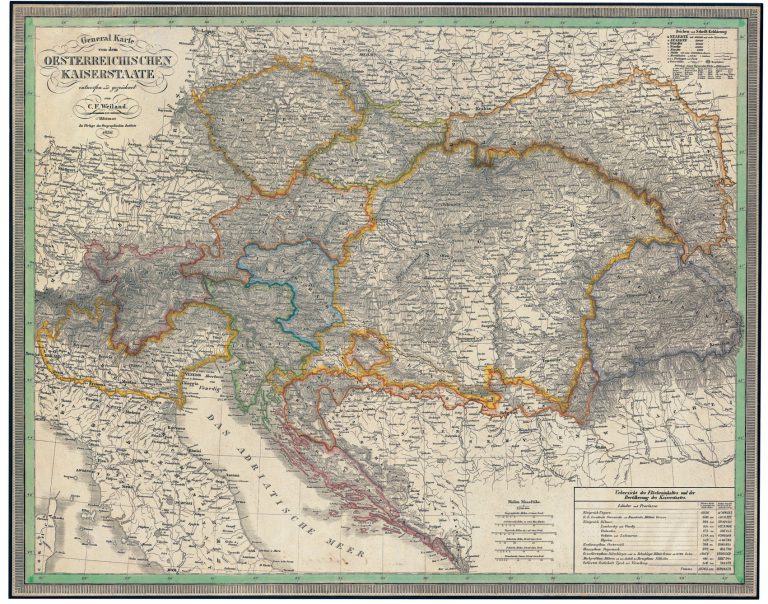

Adopting virtually the same statutes as the original institute, a number of savings banks were founded in many parts of Austria, Central and Eastern Europe, among others in: Laibach (today: Ljubljana), Innsbruck, Bregenz and Spalato (Split) in 1822, Graz and Prague in 1825, Görz (Gorizia) in 1831, Klagenfurt in 1835, Ragusa (Dubrovnik) and Kronstadt (Brasov) in 1835, Pest (Budapest) in 1839, Hermannstadt (Sibiu) and Zara (Zadar) in 1841, Pressburg (Bratislava) and Trieste in 1842, and Lemberg (Lviv), Kaschau (Košice) and Tyrnau (Trnava) in 1844. Today, one would call these banks “social businesses”: sustainable – i.e. self-supporting – enterprises that aim to fight poverty.

The 1844 “Regulations for the Formation, Establishment and Supervision of the Savings Banks” were a reaction to the resounding success of the savings bank idea. It stipulated the maximum amount of deposits and reaffirmed the objectives of providing basic financial services and preventing poverty. In addition, it formally allowed contributions to the public good, i.e. on top of the social business purpose (Volkssparkasse), donations from the profits were also permitted. Regular donations to hospitals, foundations and social institutions can be found in the accounts of the Erste from 1850 onwards.

The ”golden age“ of donation activity by the savings banks began in the 1870s, when growing profits led to a sharp increase in the amounts of reserve funds available. An average of 62,000 guilders per year was given to charitable organisations during this period. This corresponds to about 930,000 euros in today’s money. In the period up until 1914, funding equivalent to 15 million euros was made available to various Vienna hospitals.

From 1899, large sums flowed into the poor-law infirmaries and convalescent homes and into two Emperor Franz Joseph Jubilee Foundations for social housing and homes. The savings bank was also involved in cultural projects, including construction of the Viennese Music Association Building.

Following the record result in the 50th anniversary year, 117,000 guilders were accordingly allocated to charity. The Erste contributed 70,000 guilders for the construction of a children’s hospital in Leopoldstadt and a further 30,000 guilders to the St. Josef Children’s Hospital in the Wieden district. It also marked the anniversary by paying all staff a one-off bonus of six months’ salary.

For the 50th anniversary of the Erste oesterreichische Spar-Casse, a polka was commissioned from Eduard Strauss, the youngest son of Johann Strauss the Elder and brother of famous Johann Strauss the Younger. The title of his composition is “The Bee”

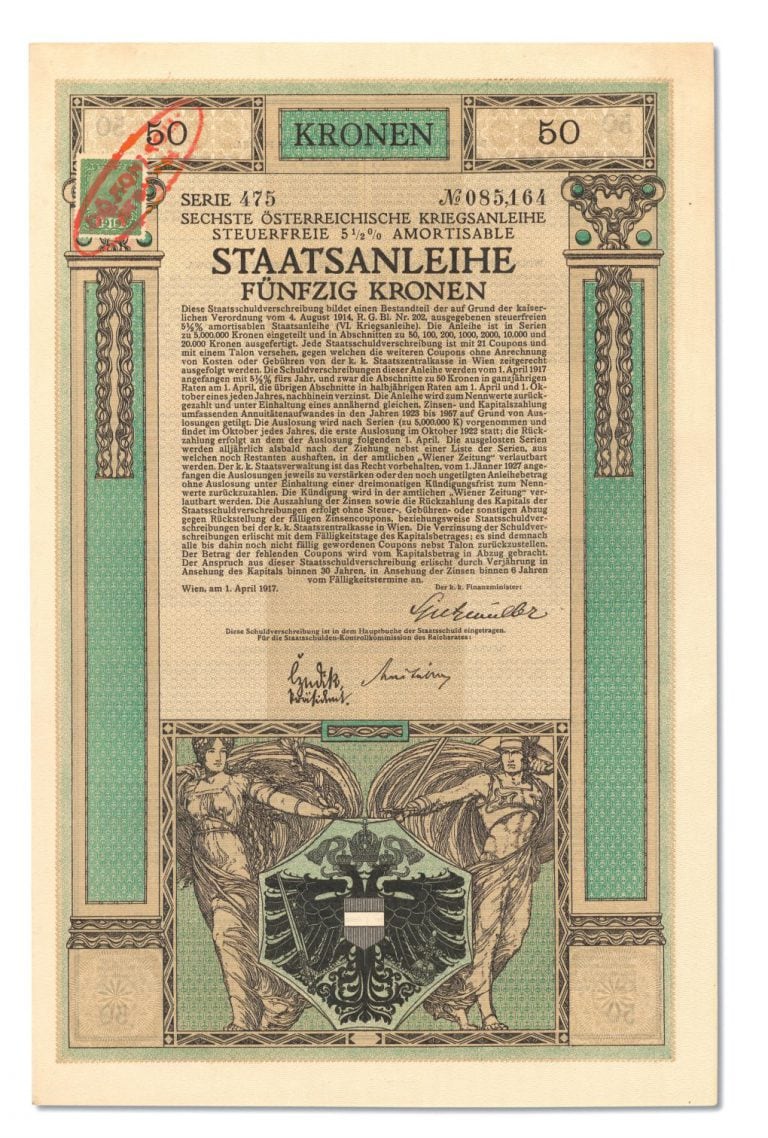

After the outbreak of the First World War, the savings banks were allowed to keep and manage war bonds, like other banks. The Erste and other savings banks thus became a systemic factor in war financing.

The Erste survived the waves of speculation in the wake of hyperinflation and currency changeover to the schilling unscathed.

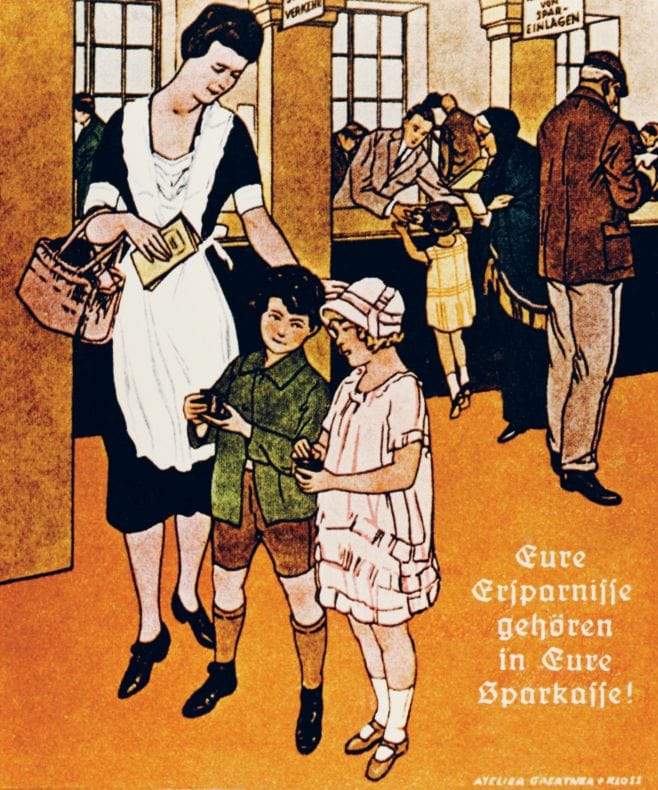

World Savings Day was introduced in Austria.

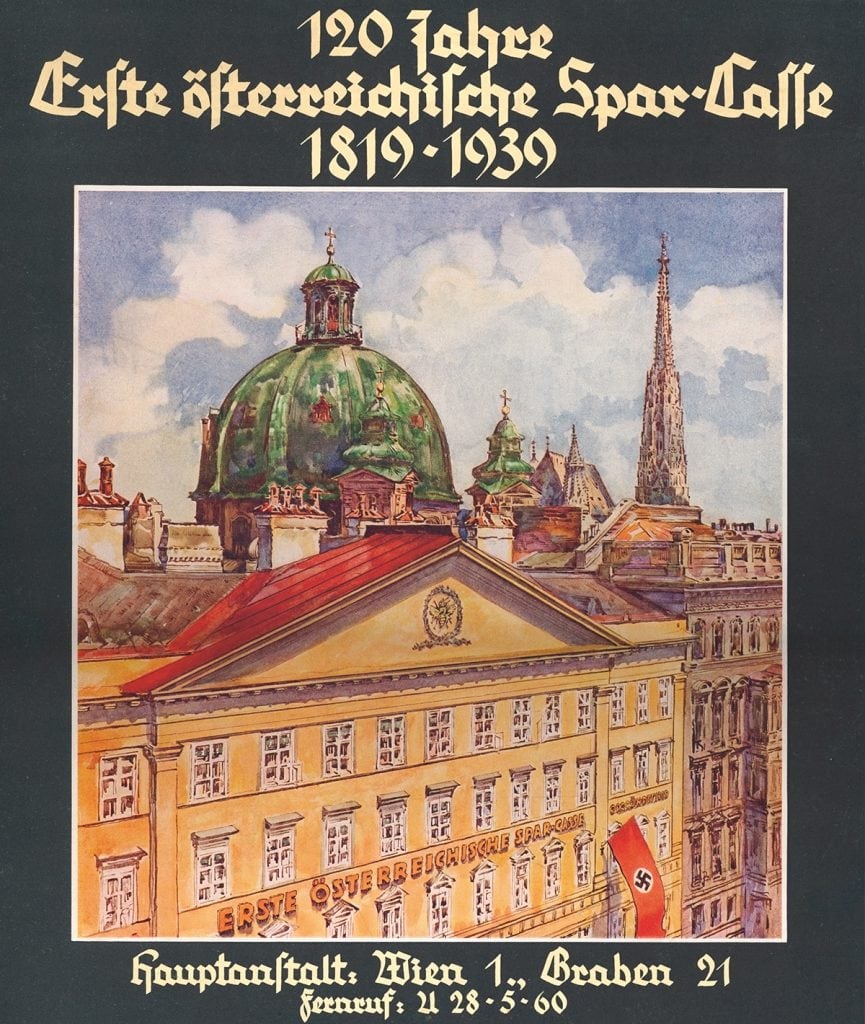

In the period of Austro-fascism and under National Socialism, the Erste – like all savings banks – became an economic instrument of the authoritarian regime.

Once again, the population’s savings helped finance the war.

The savings banks became henchmen in the task of blocking the assets of Jewish customers and helping to “aryanise” real estate and property. Between 1999 and 2007, Erste Bank commissioned historians to review the role played by its predecessor institutions during the National Socialist era. The most important results: around 320 accounts held by Jewish owners were plundered. Thirty mortgage loans were granted to pay the “Reich Flight Tax” and other levies. On five occasions, there was participation in “aryanisations” of houses owned by Jews. There were seven instances of a takeover of business premises.

All real estate was returned after 1945, or else settlements were reached. Nevertheless, the original owners suffered severe losses in value. Two-thirds of the descendants of persons affected were traced thanks to cooperation with the Jewish Community. Compensation payments totalling around 700,000 euros were made. A sum of 44,000 euros, which could not be disbursed because of a lack of information regarding persons to inherit, was donated to the Maimonides Sanatorium, a care home which looks after Holocaust survivors.

Erste Bank contributed around 6.07 million euros to the Republic of Austria’s General Compensation Fund.

The “Sparefroh” advertising figure addressed Austrian children for the first time, conveying the idea of saving in the early days of the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle).

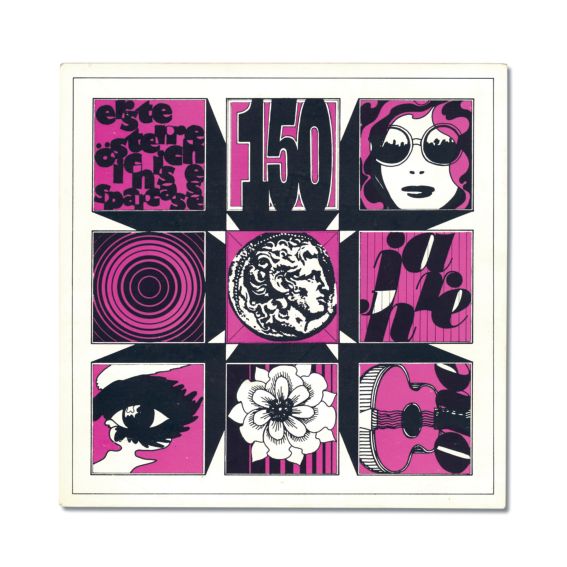

In 1969, Woodstock made music history. Queen Elisabeth II visited Austria and humankind landed on the moon for the first time. The Concorde pioneered supersonic flight for commercial aircraft. The first internet connection was established in October. And the Erste österreichische Sparkasse turned 150.

The anniversary poster is a fine example of pop art.

The Erste transferred its business operations to a public limited company. A new subsidiary, Die Erste österreichische Spar-Casse AG, was founded for this purpose. The savings bank itself was given the name DIE ERSTE österreichische Spar-Casse Anteilsverwaltungssparkasse. This kind of holding company is referred to in German by the initials AVS. It is the legal predecessor of ERSTE Foundation.

In March, Erste acquired the GiroCredit Bank AG and changed its name to Erste Bank der Österreichischen Sparkassen AG. In November, Erste Bank made Austrian financial history by floating on the stock exchange. Shares to the value of more than seven billion schillings (508 million euros) were issued. In December, the shares were included in the ATX, Austria’s main index. Erste Bank remains a heavyweight in the ATX to present day.